The reader here will find some articles on the FSM I find to be of special interest. -BTS

Full FSM Press Bibliography with links12/09/1984, The Free Speech revolutionaries, 20 years later

.............................The courtroom courtship and other romances

12/10/1984, Two decades do not dim credos of the UC rebels

.............................Chronology of the Free Speech Movement

12/11/1984, Free Speech patrimony scatter to the winds

.............................FSM leaders keep the·faith: 'Still agitating' after all these years

.............................CALENDAR OF CHANGE A Selective Chronology

12/12/1984, 'Biggest convulsion in history of education'

.............................Some standout events in 3 tumultuous years

.............................Players and bystanders in the UC revolution

12/13/1984, Those who still look for ways to escape

.............................Some 'got it,' some got Rolfed, but most steered clear of religion

12/14/1984, Nuclear war fears unite former FSM activists

.............................How Berkeley has changed since the FSM

San Francisco Sunday Examiner & Chronicle

December 9, 1984

The Free Speech revolutionaries, 20 years later

Agents of ChangeBy Lynn Ludlow

Examiner staff writer

First of six partsWhen the 1960s disappeared, so did Charlie Brown.

"The world didn't change fast enough for him," said mountaineer Bob Briggs. "He always lived on the edge."

Edge. The word comes up often in recollections of 1964, when the Free Speech Movement loosed an avalanche of political, social and cultural change.

"We were standing at the edge of the cliff," said Randall Collins, "and breaking away."

He didn't break away, not like Charlie Brown, but he doesn't throw his body onto the gears, either. He now writes books, teaches sociology and lives in a $300,000 home in San Diego.

Charlie Brown, Randall Collins and 781 other agents of change found themselves on the edge 20 years ago when the FSM occupied Sproul Hall, the administration building at the University of California in Berkeley.

For campus activists, it was the autumn of a tumultuous year. They went limp by the hundreds in San Francisco civil rights demonstrations. They escaped death during Mississippi voter drives. Non-violence, civil disobedience and pacifism were emphasized.

It was the year before opposition to the Vietnam War would alter the nature of protest, which intensified

Diego. Co in violence as the war itself escalated. And over the next five years, the protest movement would generate an unprecedented challenge to American institutions.And now 20 years have passed. What happened to Charlie? Randall? The other spear carriers?

A 20th anniversary survey by The Examiner suggests the rank-and-file demonstrators of the FSM have become—for the most part—individualists and serious overachievers.

Although the FSM veterans vary greatly, most of them conform to a profile that is professional, highly educated, politically disenchanted, liberal, non-religious, non-activist, married and, to a striking degree, independent.

Most are self-employed or self-supervised.

None of those questioned in survey is involved in sales, services, business administration, finance, industry, utilities or a life of crime.

With a range from zero to the level of extraordinary wealth, annual incomes recorded by the survey suggest an average of $34,000.

Many of the movement activists say they experimented with drugs and other diversions.

Most eventually settled down and bought homes. Some watch in dismay today as their own children choose their own forms of rebellion, such as computerland career plans or fashions that emphasize hair abuse.

Worse, few youngsters today show even a tepid interest in America's first major campus protest.

Yet many historians call the FSM sit-in the dawning of a new age of liberation. Or alienation.

Or both.

The Examiner spent three months gathering data from rank and-file demonstrators, a sample

plucked at random from the FSM arrest roster of Dec. 3, 1964.One drifter, Charlie Brown, address unknown. One author, Randall Collins, well established. Dozens of professors and professionals, entrepreneurs and artists, lawyers and

—See Page A14, col. 1

Agents of Change

On the trail of Charlie Brown and the FSM—From Page Al

homemakers. Cast forth, most of them, from Berkeley. Found in places of like ilk—like Elk, in Mendocino County, populated by refugees from the 1960s.

Collins, 43, refuses to look back with nostalgia.

"It was the age of conformism," he said. "The '50s were psychologically very oppressive. Just pick some group to conform to, and that's it. It was a vast mindlessness."

***

Charlie Brown. He's a clown.

That Charlie Brown. . .

From "Charlie Brown"

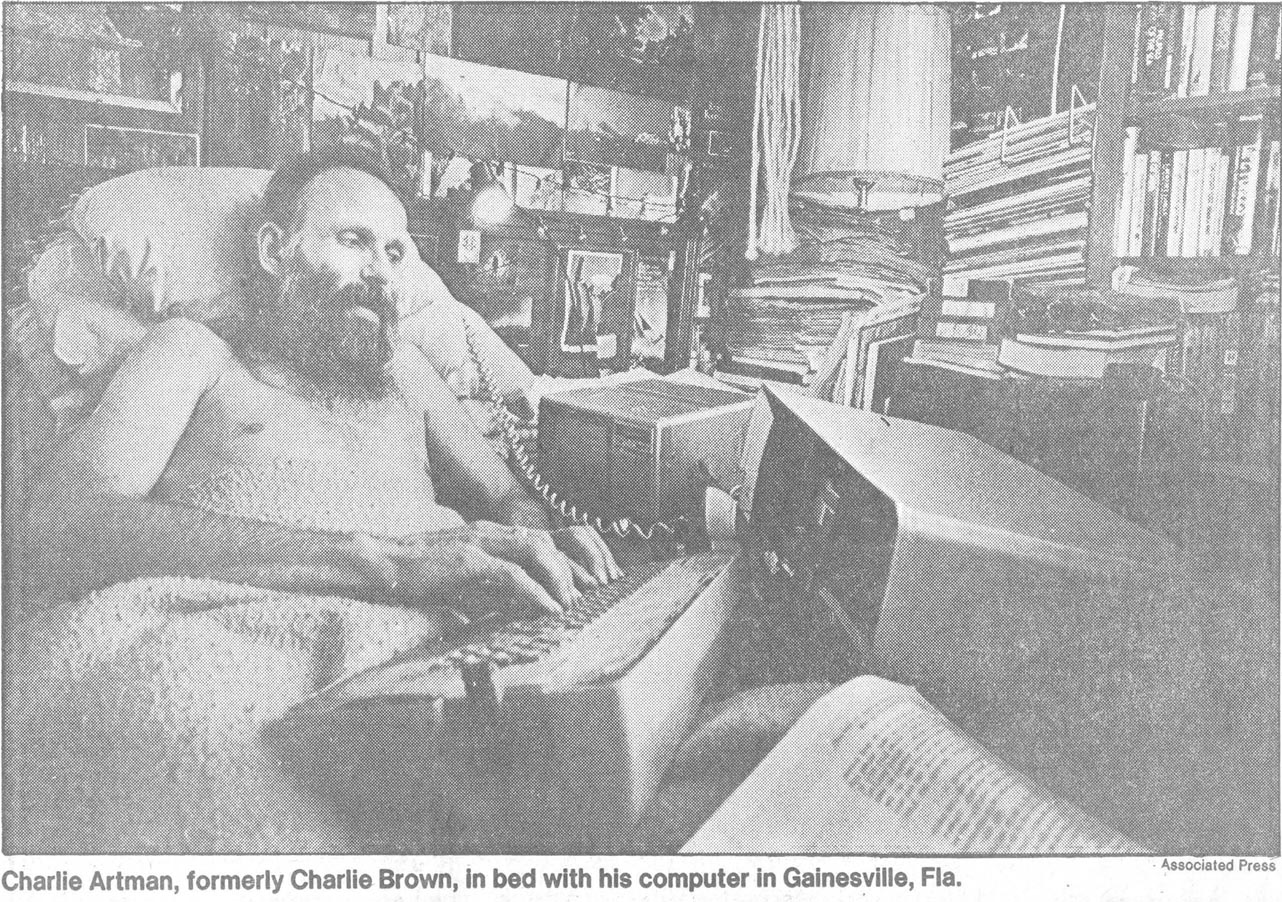

by the CoastersThe search for Charlie Brown began with a problem. It wasn't his name. He changed it from Charles Artman because, as he explained, he always wound up a loser.

He couldn't be traced through his profession. On campus he was an evangelist of psychedelia, listing his occupation as Boohoo of the Berkeley Bag.

He would have been the East Bay's first hippie, but in 1964 the term hadn't yet been coined.

"He was always trying to be the guru," said Brian Carey, an acquaintance. "He probably ended up in Skid Row somewhere."

***

About two-thirds of the FSM veterans were tracked down in two months of investigation.

Mark Desmet owns a computer company in Silicon Valley. Richard Adelman teaches people to play conga drums in his Oakland living room. Patricia Eliet teaches English at Cal State Dominguez Hills. John Reinsch, M.D., is a hematologist in Fresno.

Julie Wellings has just returned from 10 years of spiritual pilgrimage in India. Keith Simons lived on an Arkansas back·to-the-land commune. Rodney Mullen served Synanon, then left it.

In a representative sample of 58 drawn from the arrest list, only one works for the federal government (as a foreign service officer).

Only three are corporate minions. One is a copy editor at the San Francisco Chronicle. Another is the display manager of a Modesto store.

The other is probably the only Del Monte cannery foreman with a political science degree, but he needs a seasonal job. He spends the winter months with his family in Elk.

Collins prefers to work for himself.

"When I write, it's my own endeavor," he said. "If I waste time, I can only blame myself."

He is author of three books, including "The Credential Society," a critique of higher education's emphasis on degrees. Much graduate education, he asserts, is simply a way to guarantee work for employees of universities.

For a decade Collins has worked on a comparison of Oriental and Western philosophies. He said, "I was never very career·oriented."

***

... He's goin' to get caught,

Just you wait and see.

(Deep bass voice)

"Why is ever'body

Always pickin' on me?"

—From "Charlie Brown,"

by the CoastersAlthough he is far from typical of FSM demonstrators, the search for Charlie Brown was mandated by the rules for a proper statistical survey, which allows the selection of every 10th name on a list of subjects.

The problem was the 20 years between then and now. In a society that values privacy, some individuals can't be found without a court order.

And some can't be found at all. "As far as I know;' said Andrew Kent, who knew him 15 years ago in New York, "Charlie has disappeared ' from the face of the earth."

The irony is that barefooted Charlie Brown was so easy to find in 1964, when even the FSM rebels wore skull· cap haircuts and narrow ties. To them, he was something of an embarrassment. Maybe he still is.

He is remembered for passing around a peace pipe inside Sproul Hall. He often wore black robes, granny glasses and shoulder-length hair held by a head-band. He seldom wore shoes. He asked strangers to call him Little Eagle.

He proclaimed himself head priest of the Neo-American Temple of the Rainbow Path.

His views of peace and goodness were asserted with such vigor that he rarely won converts.

"Charlie was not the kind of person you would call a friend," said the Rev. Phil Zimmer, an Episcopal clergyman who knew him for a time in Wyoming. "He was ' always trumpeting a cause. People always had to send him down the road eventually."

***

''Employers will love this generation .... They are going to be easy to handle."

—Clark Kerr, UC president, 1959The times, as the song said, they were a-changin'. Marxists on campus spoke confidently of problems faced by "the post scarcity generation," a term that would later disappear. Galaxies, Imperials and Impalas threw their wide bodies across Telegraph Avenue. Suburban homes went for $499 down plus closing costs. Newspapers invariably called the Beatles "long-haired Liverpudlians."

Few questioned the notion of progress through engineering. Nobody protested when the Sierra Club pro. posed a nuclear plant as an alternative to new power dams on the Tuolumne : River. The Ban the ~mb movement ~ got as little campus support as the "fight against Proposition 14, a statewide referendum that overturned an open-housing law.

Newspapers took an indulgent view of panty raids, a diversion that migrated from the East Coast to Berkeley in 1956. Damages were about $20,000 in Berkeley's raid, but few noticed how such events often escalated from humor into near-riots against police and authority.

This was the first generation reared on television. Problems were seen, literally, in black and white and were solved in the final five minutes. Existentialism prevailed as the biggest philosophy on campus.

Collins said: "It expressed the meaningless of life but paradoxically showed that the only meaning comes from when you say, 'OK, I am responsible for what I do or don't do,' and meaning is something you create, not discover. You create it by sort of rebelling against convention."

***

Artman, Charles: #7547; appeal taken; 3 counts, stipulation; $250 or 25 days jail.The hunt for Charlie Brown, as with the other FSM veterans in The Examiner's survey, began with a paper trail of public records.

After 20 years, arrest reports and trial documents aren't available.

But still on file with the state Court of Appeal is a list of 783 people charged with trespass and resistmg arrest in Sproul Hall on the morning of Dec. 3, 1964.

Then came further checks in public records for Artman/Brown and all the FSM names in the survey:

UC records show all but a few of the demonstrators were students. Charlie is listed as an anthropology major who dropped out in 1962.

Most of the arrested students appear in the UC student directory for 1~ - but not Charlie. He Isn't listed as a registered voter in San Francisco or Alameda counties, and, unlike many in the survey, his name did not appear in phone directories for the Bay Area, Los Angeles or New York City nor in city directories for San Francisco or Oakland.

In all of them, Charlie is simply missing. And he does not hold a driver's license or own a motor vehicle in California, according to the state Department of Motor Vehicles.

However, the state Bureau of Vital Statistics in Sacramento holds a copy of a wedding certificate for Artman in 1966. He gave his occupation as "wandering priest."

The marriage was later annulled when his bride, a 19.year-old woman from affluent Kensington, com· plained about living in unfurnished cellars and the back of his truck. The situation deteriorated, she told the court, when her husband brought home two other young women one night for "illicit relations."

It's the kind of thing that could get someone in serious trouble, but his name didn't show up among the death certificates.

***

The demonstrators have used their soiled bodies, their foggy intellects only to tear down the reputation of this citadel of learning, which helped build the bomb, produce a dozen Nobel award winners. New Yorkers retched in disbelief to see on TV their bodies, a melange of beards and black socks, piled up like cattle across the corridors.

—Jim Scott, then sports editor, the late Berkeley GazetteThe force of public hostility surprised most FSM demonstrators. Some problems were immediate, others came up later.

"I flunked out," said David Tussman. He later went to a junior college, then returned and went on to law school.

Lynne Hollander said: "It made me more radical. It affected my choice of work for a long time, and my friendships."

Steve Robman was one of three in The Examiner sample to join the Peace Corps, which didn't hold his Berkeley arrest against him.

"It became," he said, "a badge of honor."

After he left the university in 1969 with his Ph.D., Collins worked as a writer, computer programmer and teacher (at the University of Wisconsin, University of Virginia, UCLA and UC·Riverside). He started a Christmas tree farm, which failed. He tried to begin an animated film business that would produce instructional aids. He is trying to raise venture capital for a computer hardware idea.

"For a while I wanted to be a psychoanalyst," he said, "but I am very satisfied with what I am doing now."

His wife is an attorney. Their combined income is about $100,000.

Other findings from The Examiner survey'

• One of every four is self-employed. Daniel Keig is a real estate mogul. David Kamornick is a lawyer in Los Angeles. Marvin Tener is a computer consultant back in his hometown, Philadelphia.

• Most of the rest are self-supervised. Michael Shub teaches mathematics at City College of New York. Joe Botkin drives a cab in Berkeley. Rodney Mullen administers a treatment center for drug and alcohol abuse in Tucson, Ariz.

• One in 10 is listed as a homemaker, but none of those seems to fit the conventional image. Ethel Jacoff Weinberger holds a teaching credential Peggy Hallum Slater has a law degree. David Wald, son of biologist and Nobel laureate George Wald at Harvard, takes care of the baby while his wife, a nurse, is at work.

• Of the others, 5 percent are students again. Michael Cortes, who worked with foundations and the national office of a La Raza organization in Washington, D.C., is back at Berkeley to work on his doctorate in public policy.

Elin Calvin, another progeny of a Nobel laureate, became a baker after she dropped out. She returned and received her bachelor's degree in philosophy, then decided to go on for a master's degree in clinical psychology.

• Only 4 percent work in blue-collar jobs or unskilled office work.

Devorah Rossman: "I didn't lightly take that risk to my academic career or personal being. It is frightening to stand up for what you believe. But for me it's necessary. It is necessary today."

***

The Charlie Brown file grew when his name, like those of other demonstrators, was checked by The Examiner's extensive library of past newspaper articles. In early 1965, Charlie Brown had jumped into the news when he declaimed enough taboo words to get himself arrested in what was known as the Filthy Speech Movement.The arrest failed to charm his fellow rebels, who predicted accurately that much of the public would confuse the right of on-campus political advocacy with the gratuitous use of forbidden verbs.

By then Brown had erected a teepee on the hill near Lawrence Radiation Laboratory. When police evicted him, he called it a temple. The revolution went one way; he went another.

In Berkeley the old grads still remember how Charlie sang a touch too loudly when they linked arms for "We Shall Overcome." His beard was too untrimmed; his hair was too long. His serape was too ethnic. When he wore a suit to court, his socks were too red.

Worse, he was too old, maybe 25 or so. Even among rebels, it was still the age of conformity, which called for conformity of age.

Someone circulated the word that Charlie Brown might be an FBI plant. In the context of Telegraph Avenue's political and cultural scene at the time, no court could have issued a sentence so cruel. Charlie was shunned by serious radicals.

Another story quotes Brown in court, telling a patient judge, "LSD is a true sacrament."

He was convicted anyway of possession of LSD. It had been stashed in a bronze cross he wore around his neck while campaigning for the Berkeley City Council in 1967.

He lost of course, and went to jail. His Berkeley days were over.

* * *

The 40-year-old looks back on himself at 20 and sees a distant relation, a person whose ambitions, affections, triumphs and fears seem slightly absurd.

—Ron Fimrite, the writer, in an article about the late Jackie Jensen, an athletic hero at Cal.

The FSM demonstrators came from different places and different backgrounds.

Mark Switzer, who attended a high school in Arizona with 110 students, suffered something like culture shock when he joined 27,000 others on the Berkeley campus in the fall of 1964. Marvin Tener came from Philadelphia, son of working class immigrants from Russia. Stephen Leonard's parents "were committed activists." The father of Ronald Hargreaves disapproved of civil disobedience.

At the time, a UC survey of FSM students showed that many of their parents came from service and labor-type jobs as from management or teaching. The median age was 21. Of the 783 who were arrested, 688 were registered students. The total included 141 graduate students.

A third of them were majors in social sciences, particularly political science, history and psychology. Only 1.65 percent were enrolled in professional schools.

A questionnaire-type survey at the time resulted in a well-publicized report that FSM demonstraors ranked higher scholastically than other students, but the actual grades were about the same.

Grades don't always reflect intellect. Hargreaves, an average student, had IQ scores of more than 150. For some, like mathematician William Knight, the FSM trial was resented because it cut into study time. In that semester, he said with regret, he received his only B.

As for Collins, his boyhood was spent in the rubble of postwar Berlin, where his father was posted by the State Department.

"My earliest memories are of the bombed-out city, the ruins," he said. "I can remember when we lost our dog. And Mom explained it was probably eaten by Germans because they were starving."

***

Earl Durand, Earl Durand,

Born too soon a mountain man

Shot down in the Tetons

By the law's bloodthirsty hand.

—From "Teton Tea Party"

sung by Charlie (Artman) BrownCharlie Brown's trail had, grown cold by 1984.

Jim Wood, The Examiner's food editor, found a Folkways recording, ''Teton Tea Party." The vocalist, accompanying himself vigorously on the

—See next page

From Vermont to Vishnu: Radicals' lives after Berkeley

—From preceding pageautoharp, was Charlie Brown.

The path led to Brooklyn. Publicist Andrew S. Kent said he produced the recording in 1967.

This was a long way from a secluded camp in the Grand Tetons, where rock climbers gathered in the 1960s. Kent said they would sing folk tunes and drink a semi-lethal cocktail called Teton Tea, a mixture of vodka, wine and anything left on the shelf.

"Lovely, lovely evenings," said Zimmer, now vicar of an Episcopal church in Twenty-Nine Palms. "People came from all over and exchanged music. Damn good music, too."

Charlie Brown, who had arrived in Jackson on a motorcycle In the late 1950s, particularly liked the tune about Earl Durand, a Wyoming individualist who died in a shootout.

Bill Briggs, a climber and songwriter usually credited with starting the Teton tea parties, recalled how Charlie behaved on what was, literally, the edge.

"When he took up rock climbing, he took foolish risks," he said. "He gave it up before he got killed."

When the Boohoo of the Berkeley Bag returned to Jackson in the early 1970s, Briggs said, he had changed with the times.

"He was dressed like Merlin the magician," said Dick Barker, another Wyoming acquaintance. "He said he was the reincarnation of Black Elk, or something. He is the most weird person I ever met."

Briggs said Charlie had returned to Wyoming in an ecumenical quest to bring all religions together.

Citizens of Jackson were unsympathetic. "He was more or less run out of town," said Briggs.

***

This chrome-plated consumers' paradise would have us grow up to be well-behaved children. But an important minority of men and women coming to the front today have shown they will rather die than be standardized, replaceable and irrelevant.

—Mario Savio, FSM spokesman inside Sproul HallSteve Robman sold chrome-plated toasters at Bloomingdale's during one bleak Christmas season, but he has worked steadily ever since as a movie director.

He tends to pick material that matches his political interests, such as an educational film about the Sandinistas, "Talking Nicaragua," with Susan Sarandon.

Mark Switzer chose instead to sail to the South Pacific, where he remained for five years. When he returned, he worked for environmental causes. Then he married, quit, took his savings and built his own home in 'Inverness. Last September he and his wife adopted a baby.

Elizabeth Blum moved to Vermont, became an occupational therapist for the local school district. She calls herself the house radical.

Shelagh Hickey Covington, who married a Chicago attorney, said she has become involved in three volunteer activities.

"First is a medical center in Chicago. I was president of the auxiliary board of the (Chicago) Art Institute. Thirdly, I am a director of Lincoln Park Zoo," she said. "People, paintings and animals."

Ronald Hargreaves, then working as a researcher for a sociology professor at UC, took his backpack above the campus in 1972 and killed himself with a revolver.

He would be the first of two suicides In the FSM statistical sample. The other, Anya Allister Sagara, killed herself a year ago in Berkeley. Both deaths were blamed on acute depression.

***

The chain of inquiries into Charlie's whereabouts led from Briggs to Steve Larson, one of the Teton climbers who now lives in New Paltz, N.Y. Larson mentioned Brian Carey in New York City.

Carey suggested Steve Roper in Oakland.

No, said Roper, he hadn't seen Charlie in 15 years or more.

Gloom.

But two years ago, he said, he saw a letter to the editor in Newsweek. It was signed by a Charles Artman.

Excitement.

At the magazine, a cordial librarian hunted up the letter. The return address was in Gainesville, Fla.

Jackpot.

Charles Artman was in the phone directory.

A voice with Midwestern flatness:

"Hello?"

"Is this Charles Artman?"

(Pause.)

"Yes."

"Is this Charlie Brown Artman?"

(Laughter.)

"Yes."

(The purpose of the call is explained)

"How in the f--- did you ever find me?"For now, the Rainbow Path ends in a small house trailer. On the walls are pictures of Jesus Christ and the Guru Maharaj-ji. Fish swim in glass tanks, the age of Aquarius.

Charlie is 45 years old, a student again. He is working on his undergraduate thesis in anthropology at the University of Florida. The subject is the evolution of consciousness, which he has printed on an endless scroll of computer paper.

"There is no mass, no time, no space," he said, "only bits of energy flitting around."

Nobody flitted with more energy in a life on the edge. In the late 1950s, Charlie had performed Pete Seeger songs, climbed rocks with dangerous abandon, drove a motorcycle wildly and drank from the wining jug, just like Jack Kerouac. In the 19605, he moved to Berkeley, joined the FSM protest, dropped acid and became a hippie.

After departing Wyoming in 1973, he said, took his quest to Denver, Salt Lake City, Europe and Miami. He followed the Mallaraj-ji.

"In a few years you might find me active again," he said. "Right now I am just taking a breather."

He hasn't taken an acid trip since 1969.

"Psychedelics are an important part of my evolution," he said. "Drugs and Scientology are responsible for where I am today."

He split up with his second wife, who lives in Miami with their 9-year, old son. He hopes to begin graduate work at Chico State University after he completes his bachelor's degree, but he is vague about the timetable.

His name is Artman.

It's the 1980s, and computers happen to be on the edge. Charles Artman is fascinated. He was in bed, working with his own household computer, when the phone rang.

He said, "I am waiting for a computer that will sit up and say, I think, therefore I am.'"

The Rainbow Path is only a memory. Charlie no longer despises organized religion.

"I still have long hair, but I'm not running around in a costume anymore," he said. "I do wear shoes to church."

Every Sunday, Charlie attends formal services at the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

He said he wants to be baptized as a Mormon, but his application is pending. In the meantime, he keeps busy by filing suits against the food-stamp bureaucrats who cut him off.

Twenty years after the Sproul Hall sit-in, the former Charlie Brown said people cannot change things through politics. The only meaningful change is spiritual, he said, by "plugging into the source of all creation."

He doesn't have a job. Since 1979 he has survived on $314 a month from SSI, or Supplemental Social Income, paid by the federal government to the disabled.

"I am," he said, "a burnout case."

***

"I don't think much about the past," said Collins. "I'm surprised at all the attention paid to the FSM. I hope people don't treat it as nostalgia."

His daughter went off to college this semester.

"A lot of people are down on kids today," he said.

He didn't mean young people are misbehaved. On the contrary.

"I think they have the potential for trying to put themselves in action for good causes," he said.

"As we did."

The courtroom courtship and other romances

Ethel Jacoff met Michael Weinberger in the courtroom where they stood trial during the 1964 Free Speech Movement at the University of California in Berkeley.

Twenty years later she would remember her arrest ("so terrible") and the jail ("subhuman"), but her memory of court had turned to courtship ("a romance of the FSM").

A survey of the 1964 demonstrators by The Examiner shows most eventually got married, settled down and reared families—not necessarily in that order.

Almost 20 percent of FSM participants, like Ethel and Michael, married each other.

That’s an extrapolation. But of 49 men and women in a statistically valid sample, nine were married then or later to others who were arrested in Sproul Hall.

Only three of these marriages survived.

Compared to a similar demographic group, FSM veterans are less likely to be married now (75 percent to 52 percent) and more likely to be divorced without remarriage (23 percent to 14 percent).

Of the FSM sample, 4 percent are men and women who live together and 6 percent are lesbians with long-term relationships. No comparable figures were available from the comparison group.

Sixty-seven percent of the FSM demonstrators became parents. It's a figure higher than they might have predicted 20 years ago, but well below a national average of 84 percent for people of comparable age and education.

Joseph LaPointe, 50, a professor at New Mexico State, is the only grandfather in The Examiner's FSM sample of 49. Dana Kramer-Rolls has three step-grandchildren.

Many FSM veterans waited until their 30s to have children. More than half the kids are 12 or under.

"I didn't even get married until my early 30s," said Stephen Leonard, an assistant attorney general in Massachusetts and the father of two children, aged 7 months and 4 years: "I had a good time for a number of years."

He paused, then added: "My wife already knows about that."

Other comments on families, romances and marriage:

Martha Platt Bergmann —"I won't remarry unless I'm absolutely sure .... I have a close circle of friends who are just super. Like the root system of a plant, if something should happen to one root, I wouldn't go under."

Julie Wellings —"I live with another woman and am helping to raise a child. We have a committed relationship."

Ethel and Michael Weinberger, who were married 18 years ago, moved back to rural Vermont. He is an architect; she will resume teaching once her 3-year-old is off to school.

"I can now understand my parents' point of view," said Ethel. "It was worry."

She remembers they were "mostly frightened and horrified and supportive but thought it was dumb to get arrested."

And now it's her turn.

"I think about it in terms of my own 14-year-old son," she said. "How will I feel if my son goes through something like this?" He probably won't. She described him as far more conservative.

"And I would want him to participate in demonstrations."

WAS IT WORTH IT?

(figures in percent)

Yes 90

No 2

Don't know 2

No comment 6Remarks:

"It was a real catalyst moment for both the university and the whole country..."

—John Huntington, English professor"Yeah. It is hard to figure out all the consequences, though, including negative consequences. For example, Ronald Reagan came into government partly on the backs of the FSM—now he is in the White House. Ed Meese, Lowell Jensen and others came to prominence during the backlash. "

—Patricia Eliet, English professorBased on a representative sample of FSM activists.

PLACE OF RESIDENCE

(figures in percent)

Berkeley 12

Other Bay Area 26

Other California 17

East Coast 22

Midwest 8

South 3

Southwest 1

Northwest 3

Out of the country 2Remarks:

"Among people in Berkeley .there's a trend toward gourmetism, hot tubs, etc., a hip, rich lifestyle.

It's not the way I want to go...."

—Keith Simons, importer in Portland"I came to Vermont and left Berkeley even before People's Park. I wasn't comfortable with the violent turn political action had taken."

—Ethel Jacoff Weinberger, former teacherBased on a representative sample of FSM activists.

ARREST IMPACT ON JOBS

(figures in percent)

Positive 13

Negative 27

No effect 44

Not Sure 16Remarks:

"No. On the contrary, it was a plus. In my job, teaching school at Bethesda,·they really liked it. Others, it didn't hurt. It makes me feel good;·when people find out I was in the FSM, they get all excited about it."

—Kenneth Barter, alcohol education counselor"I wanted to be a teacher and applied at the Chicago Board of Education for an assistant teaching position. I went in and told them about the FSM arrest and they told me (in summer '67) that I was not suitable."

—Shelagh Hickey Covington, civic leaderBased on a representative sample of FSM activists.

ANNUAL FAMILY INCOME

Highest: $200,000+

Average: $33,875Income level

(figures in percent)

FSM USA

Under $5,000 7 1

$5,000 to $9,999 11 2

$10,000 to $14,999 4 4

$15,000 to $24,999 21 28

$25,000 to $34,999 21 31

$35,000 to $49,999 18 20

$50,000 and over 18 14Remarks:

"Money is abused more than any other substance. People think that making $15,000 a year is OK, but $30,000 will make them twice as happy."

—Kenneth Barter, alcohol education counselor"Money…conveys freedom. It is not a value in itself but lets you play the games you want to play."

—Daniel Keig, real estate investor

FAMILY

Income level

(figures in percent)

STATUS FSM USA

Married 52 76

Never married 19 7

Divorced 23 14

Separated 4 3

Widowed 2 1Remarks:

"Married. Only once. Probably one of the few (FSM veterans) married continuously for 16 years."

—Keith J. Simons, importer"I have lived with a woman for 12 years. Does that count as an alternate lifestyle?I guess not. Oh, well…"

—Steve Robman, stage directorPARENTS

Any kids? FSM USA

Yes 67 84

No 33 16How many?

One child 34

Two children 38

Three children 28

More than three 0How old?

Under 5 19

5 to 12 36

13 to 18 29

19 to 22 10

Over 22 6Remarks:

"I had a grandson born last week. What kind of world do we want them to inherit? Not 1984."

—Joseph LaPointe, biology professor"I’d still like to have the wife and kids. Always thought revolutionaries should have kids. People who shape a society should understand the importance of another human life."

—Joe Botkin, taxi driver (single)

HOME OWNERSHIP

(figures in percent)

Yes 62

No 38HOME VALUE

Median value of homes in the sample $100,000

Average value $152,560Remarks:

"No home. No car. What we had was pretty well cleaned out by the divorce."

—Michael Cortes, UC graduate student"It’s worth about $65,000. In San Francisco it would be worth half a million."

—Gordon Bergsten, economics professorBased on a representative sample of FSM activists.

Still to come in FSM series

IN TOMORROW'S EXAMINER

—Twenty years later, our survey shows former Free Speech Movement activists still believe strongly in a student's right to hear and experience political advocacy.TUESDAY—Disenchantment with politics has led most campus rebels of yesteryear into political inactivity. Most vote for Democrats, but a few have signed up as Republicans.

WEDNESDAY—They marched into Sproul Hall to shut down the odious education factory, but today a surprising percentage of FSM veterans are professors, teachers or university workers.

THURSDAY—After the exhilaration of the FSM, many activists rejected conventional lifestyles and searched for other ways to achieve goals of personal and psychic liberation.

FRIDAY—The FSM veterans worry about the environment, social inactivism and Nicaragua, but agree with surprising unity on the major issue of the 1980s—nuclear war.

The research and the researchers

Statistics in these reports come from an Examiner survey based on a random sample from 783 names on a list of Free Speech Movement activists arrested on Dec. 2-3, 1964.

Most results are based on questionnaires and in-depth interviews with a final survey group of 49. In some cases, the base number is · larger. The potential sampling error is plus or minus 16 "at the 95 percent confidence level." This would indicate it is reasonable to draw some basic inferences.

The "USA" comparison group, sharing similar age, race and education with the FSM sample, is a "selected subset" of 131 respondents from a 1980 study by the Center for Policy Studies at the University of Michigan.

Professor Richard Deleon, director of the San Francisco State University Public Research Institute, and Ed Emerson, a graduate student, generously helped with consultation and data preparation.

This series was researched and written by reporter Lynn Ludlow, who was involved 20 years ago in coverage of the FSM. He was assisted by staff writer George Frost. Series editor was deputy metropolitan editor Eric Best.

Researcher / reporter Jacqueline Frost, now with the Monterey Peninsula Herald, found Charlie Brown.

San Francisco Examiner

December 10, 1984

Two decades do not dim credos of the UC rebels

Agents of ChangeBy Lynn Ludlow and George Frost

Examiner staff writers

Second of six partsMany a Berkeley activist of 1964 paid a buck to hear the lectures of Hal Draper, a Marxist theorist who took a sardonic view of the Free Speech Movement.

Within a few years, he said, most of the rebels arrested Dec. 3 at the University of California would be "rising in the world and income, living in the suburbs, raising two or three babies, voting Democratic and wondering what on Earth they were doing in Sproul Hall—trying to remember, and failing."

Draper was wrong about their memory.

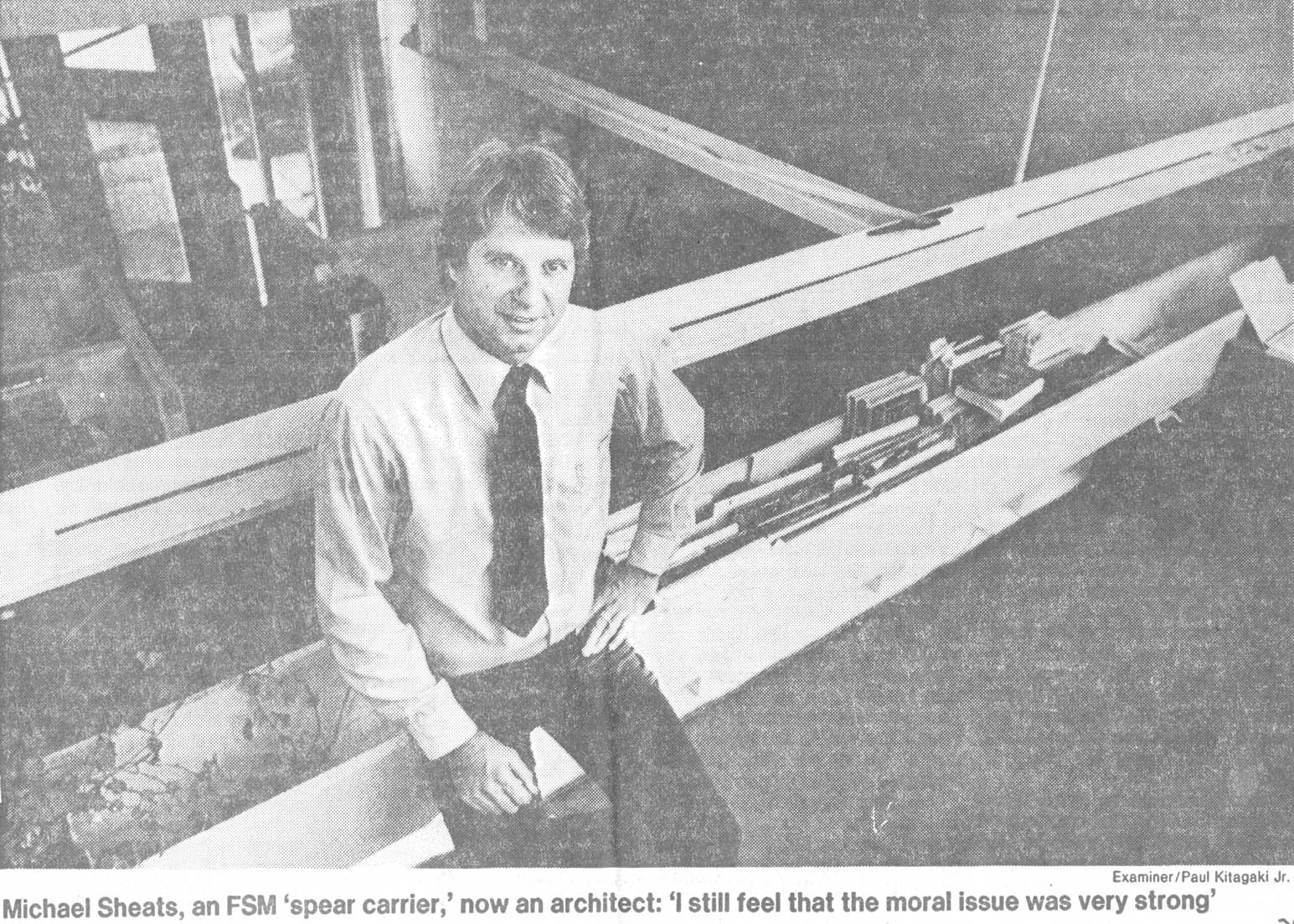

"The issue was the First Amendment right of free speech," said Michael Sheats, 38, now an architect. "The administration was trying to control political expression."

Similar answers came unhesitatingly from 71 percent of the men and women who were interviewed as part of a 20-years-later Examiner survey of the FSM's rank and file.

Most of those in the minority said free speech was only a part of some broader issue, such as civil rights. Sheats, no Mario Savio, was 19 at the time. He left the oratory to others when he sat down along with 782 others in the corridors of power.

"I was-a follower," said Sheats, who lives in Berkeley and calls himself a liberal Democrat. "I was just one of the spear carriers."

The spear carriers of 1964 haven't abandoned their position. Most of those in the survey sample still say that First Amendment rights extend to such controversial campus possibilities as revolutionary communists, Nazis and U.N. Ambassador Jeane Kirkpatrick.

On the other hand, only half the free speech rebels say they would go along with on-campus showings of bondage films, which several described as the ultimate test of the First Amendment:

"I still feel," said Sheats, ·'that the moral issue was very strong."

Julie Wellings, artist: "Any group that advocates violence should be protested but probably not banned."

David Wald, cabinetmaker: "Ba-

See Page A4, col. 1

Legacy of the FSM: Free speech still an issue

—From Page Al

sically, I'm against censorship."

Barbara Zahm, filmmaker: "This is a difficult question. I believe in free speech. I'd rather allow these destructive ideologies to be allowed to advocate than be threatened with censorship and tyranny. Individual liberty must be guarded."

Donna Watson, electrician: "I don't totally disapprove of hecklers. I think it's OK to shout."

Sheats shrugged and said, "Where do you draw the line? In a way, giving them the opportunity dissolves their mystique."

***

On university grounds open to the public generally, as may be defined in the campus regulations, all persons may exercise the constitutionally protected rights of free expression, speech, assembly, worship and sale of non-commercial literature incidental to the exercise of these freedoms.

Such activity shall not interfere with the orderly operation of the campus and must be conducted in accordance with campus time, place and manner regulations.

This paragraph, known as Section 31.14 of the official UC rules for 1984, is the legacy of the FSM.

Today when student groups reserve the Sproul Hall steps or the Lower Plaza for noon rallies, the university supplies the public address system, a technician and a plainclothes police officer.

Regulations spell out approved locations for the tables where student groups solicit volunteers and funds.

Nothing whatever is said about the content of speech, literature or other political activity.

It's a freedom taken for granted, perhaps because students of history often ignore the history of students.

The situation was considerably different under the late Robert Gordon Sproul (rhymes with growl), who became UC president in 1930. He didn't have a doctoral degree, but he grew up on the tough streets of the Mission District in San Francisco. During the next 28 years he sealed off the campuses from the interference of a world sometimes hostile to intellectual inquiry.

To keep the politicians on the outside while he built one of the world's great universities, Sproul banned anything that might appear to lend the university's name to off-campus issues. If the university were to get nonpartisan financial support from all the citizens, he wouldn't allow anyone to use the campus for partisan politics.

The first test came in 1934. This year marks the 50th anniversary of the lemon pie incident.

It was the nadir of the Depression. Throughout the nation, campuses had become forums for prophets of radical change.

At the Berkeley campus, rallies took place on a city street, Telegraph Avenue, which then extended north to Sather Gate.

In October, a free speech controversy arose over Sproul's summary suspension of five UCLA student leaders, including the student body president, for "alleged communistic activities." They had violated Sproul's rules by meeting on the campus to discuss statewide election issues.

Sympathizers in Berkeley called a "strike," which was actually a one-hour classroom boycott. It was strongly opposed by university officials, but more than 1,000 students gathered anyway outside Sather Gate.

According to California Monthly, the UC alumni magazine, the protest speakers were immediately shouted down by squadrons of hecklers.

"We have a Constitution," said a woman speaker, "that guarantees free speech and assembly."

Tomatoes and eggs splattered all around her. She began to cry.

"You might at least have the courtesy to listen," she said.

That's when a heckler had second thoughts about his lemon pie.

He didn't toss it. Instead, he broke it up and passed out the pieces "as a form of nourishment."

An investigation later showed 22 of the fraternity men at the event were volunteer agents for the American Legion's Americanism Committee.

It could have been worse.

In 1932, soldiers and sailors beat up students attempting to pass out antiwar leaflets outside the Army-Navy football game in Memorial Stadium.

In 1933, home-made tear gas bombs injured a member of the Social Problems Club as he sold its newspapers outside Sather Gate.

Among the interested observers in 1934 was a Quaker graduate student named Clark Kerr, who would get his doctorate in economics in 1938. The atmosphere changed. About 1,200 students heard Lillian Hellman a peace rally in 1938.

By 1941, 3,000 turned out for the last anti-war rally. It was said to be a success, but many pacifists like Kerr never forgot the day the Nazis invaded Russia. Many mimeograph machines of the peace movement began publishing demands for a second front.

Within a year, in any case, radicals and fraternity boys would all be in uniform.

And when the GI Bill veterans returned in the late Forties, they expressed scant interest in 'Overturning Sproul's network of regulations. These included the controversial Rule 17, which required his personal permission for any campus event involving off-campus political figures.

With the Fifties came the loyalty oath controversy, which brought Kerr to prominence as a liberal faculty opponent of the oath.

Sather Gate rallies were no longer possible after the university purchased both sides of Telegraph Avenue, extending the campus to Bancroft Way.

Several political leaders, including Richard Nixon and Adlai Stevenson, were obliged to speak to students from sound trucks on city streets.

"It appears strange to us and a little bit disillusioning," says the Daily Californian in a 1958 editorial, "that any university should have to take such an effort to relocate speakers off the Campus."

Although Kerr managed to liberalize the rules by 1964, content of speech was still regulated. Neil Smelser, a sociology professor and former president of the Academic Senate, said later, "The FSM and its aftermath were a series of accumulated small events, the import of which we were never aware of as it kept unfolding."

The "Bancroft Strip," a 26-foot section of sidewalk, had become the university's unofficial Hyde Park where activists would set up card tables for political literature and signup sheets.

Then someone complained about recruitment of student volunteers for Gov. William Scranton of Pennsylvania, the only serious opponent to Barry Goldwater at the Republican National Convention in San Francisco. Records showed the university owned the strip, not the city.

When the fall term began, university administrators ordered student groups to quit recruiting and raising funds for off-campus causes. The subsequent protests led to changes, but the orders were ultimately defied by activists who contended that students should not bargain away their First Amendment rights.

When students were cited, the result was a 10-hour sit-in Sept. 30 in Sproul Hall. It ended after eight students were suspended by Chancellor Edward Strong. On Oct. I, campus police arrested a former graduate student, Jack Weinberg, for distributing materials from CORE (Congress on Racial Equality). Other students surrounded the police car, which was trapped (with Weinberg inside) for 32 hours. As hundreds of police gathered nearby, the incident ended with an agreement between student leaders and President Kerr.

Kerr refused to bend on rules against solicitation of funds or recruitment of volunteers for illegal activities away from the campus, such as the sit-ins at the Sheraton-Palace Hotel in San Francisco.

Kerr, perhaps remembering Sather Gate days, also said the hard-core demonstrators included "at times as much as 40 percent off-campus elements." Among them were identified Communist sympathizers, he said. The remark was seen by FSM leaders as classic red baiting.

The FSM had little support from student government or the Daily Californian, but noon rallies began to draw large crowds. The crisis came when Strong went ahead with plans to suspend FSM leaders.

The all-night sit-in at Sproul Hall Dec. 2 and 3 resulted in 783 arrests on the orders of Gov. Edmund G. Brown. Kerr, noted as a mediator and compromiser, then took over from campus officials and called a special convocation a few days later in the Greek Theater. He announced plans to work out more liberalized regulations. But FSM spokesman Mario Savio was dragged from the stage after he tried to take the microphone. Eventually, Savio was allowed to make an announcement, but the professors were shocked.

The faculty voted overwhelmingly on Dec. 8 to urge an end to restrictions on the content of campus political activity.

The UC regents met in December to adopt provisional rules, which allowed students the same right as all citizens to engage in activism without having to get a note from their dean.

The impact reached far beyond Telegraph Avenue.

"It spread to other institutions and became worldwide," said Strong, who lost his job as chancellor.

Lewis Feuer, a sociologist whose views became so unpopular on Sproul Plaza that he departed for Toronto, wrote a fat book called "The Conflict of Generations." It linked the FSM with other notable events involving students, such as the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand.

Feuer wrote, "'Berkeley' became a byword throughout North America for a generation running amok ... a symbol for student generational militancy."

The Sproul Hall sit-in may have been the first major campus protest action, but it wasn't the last. Hundreds of demonstrations broke out against the Vietnam War, the draft, military recruiting and racial discrimination. The New Left was born in 1962, spread out by 1965, mushroomed by 1967 and disintegrated by 1969 into quarrelsome factions. The war continued.

The National Student Association estimated 221 demonstrations by 40,000 students at 101 campuses in the first six months of 1968 alone.

The FSM was significant, said Professor Smelser.

"It was one of those historical incidents that will forever shape the memory, and to a degree, the institutional life of the university."

At the time, he added, nobody but the FSM leaders appreciated the importance of their victory.

"The movement fragmented almost immediately," he said.

The fragments included Sheats, who said he dropped out of activism within a relatively short time.

Sheats remembers the FSM. Vividly.

"It was a whirlwind of power," he said. "Once you touched it, it was hard to study for your history midterm."

During the Christmas break in 1964, the Board of Regents met to reconsider the Sproul-Kerr rules that prohibited most campus activism.

Sheats went home one night and found himself shaking hands with the blue-suited dinner guests of his father, Paul H. Sheats, then dean of the university statewide extension system.

The visitors were the distinguished chancellors from other UC campuses, intensely curious about the Berkeley situation.

Mike Sheats was a certified lawbreaker.

"It was an awkward dinner," he said.

"Then the guy from Davis Mrak) asked what I thought. So I gave a little speech. It ended up we could understand each other."

The FSM arrest was his first and last.

"Afterwards, everything became too diluted," he said. ''Those marches in the 1960s were great, but now I follow more my own career. I feel my work for change is best within the context of my profession."

Still to come in FSM series

TOMORROW—Disenchantment with politics has led most campus rebels of yesteryear into political inactivity. Most vote for Democrats, but a few have signed up as Republicans.

WEDNESDAY—They marched into Sproul Hall to shut down the odious education factory, but today a surprising percentage of FSM veterans are professors, teachers or university workers.

THURSDAY—After the exhilaration of the FSM, many activists rejected conventional lifestyles and searched for other ways to achieve goals of personal and psychic liberation.

FRIDAY—The FSM veterans agree with surprising unity on the major issue of the 1980s. Their generation and their children, they say, face annihilation in event of nuclear war.

WHAT WAS THE MAIN ISSUE OF THE FSM?

(Figures in percent)Right to advocacy on campus...........................70

Free speech as part of broader issues...............25

Other.................................................................5Remarks:

"It had limited aims. To tell the administration that we should have the right to solicit funds for the civil rights struggle in the South: I was not fighting a multiversity or a stifling bureaucracy. I loved the university back then."

—Gordon Bergsten, economics professor"In a sense (the main issue) was the corruption of the university. (Oakland Tribune publisher William) Knowland didn't like the demonstrations, and the university acted to pacify him. The people who ran the institution were immoral, repressive agents of the large corporatlons!'

—Michael Marcus, Portland attorney"It was a basic First Amendment issue."

—Ethel Jacoff Weinberger"There Were different issues for those involved. I was involved in the civil rights movement. For the university the issue was to keep on the good side of the governor and Legislature. For students, it was the right of political expression on campus."

—Jeremy Bruenn, biophysicistTHE 1984 PERSPECTIVE

Do you see the issues differently today?

(Figures in percent)Yes.................24

No..................74

Don't know.......2Remarks:

"No. That's one period of my life I'm certain of. Now my actions are more personal, less idealistic. Now my responsibility is to raise three kids and make their life better."

—Peggy Hallum, homemaker"No. It may be that the activity we engaged in then planted a seed that was later carried into careers and more traditional activism."

—Martha Platt Bergmann, gardenerBased on a representative sample of FSM activists.

FREE SPEECH ON CAMPUS

(Figures in percent)Should it apply to: Yes No Don't know

Revolutionary communist groups 98 10 2

U.N. Ambassador Jeane Kirkpatrick 93 5 2

Films of women In bondage 55 31 14

American Nazi Party and KKK 88 12 0Remarks:

Revolutionaries

"Yes. You can't have it one way and not the other. Truth stands on its own two·feet. Let it speak. The false will fall to the ground.

—Dennis Peacocke, ministerNazis and KKK

"I don’t believe in free speech for groups that advocate genocide."

—David Bacon, union organizer"The movement was more a power struggle than a First Amendment issue. But, yes, we have to let them on campus."

—Marvin Tener, computer consultantJeane Kirkpatrick

"When a government official comes to campus and is booed, that can be more in the line of a public demonstration. They generally have no trouble having their views known."

—Michael Shub, mathematician"I don’t think people should stop her from speaking but they have the right to put up their placards and ask her some questions."

—Keith Simons, importer"Yes. She should have the same rights of speech. But not freedom from heckling. You can’t enforce anti-heckling without abridging freedom of speech."

—Mark Switzer, environmentalistBondage films

"That is a hard one. I guess I would have to day yes—but women would have the right to picket and urge people not to attend."

—William Knight, mathematicianBased on a representative sample of FSM activists.

page A5

60 years of protest: Chronology of the Free Speech MovementPROTESTS

A Selective Chronology: 1906-19631906

• "The revolution is here," says writer Jack London, who might be called a UC dropout. He becomes the favorite lecturer of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Members include Walter Lippmann and Paul H. Douglas. London, who toured the nation, concluded, "Stop it if you can!"1920

• Upton Sinclair, author of "The Jungle" and a sometimes Socialist candidate for governor, is denied the right to speak at UC-Berkeley.1948

• Former Vice President Henry Wallace, presidential candidate of the Independent Progressive Party, is refused permission to speak at UC.1951

• UC regents ban Communist Party speakers from campus.1959

• UC administrators forbid student government leaders from speaking "for students" on off-campus issues.1960

• In February, four freshmen at North Carolina A& T stage the first "sit-in" at a whites'only lunch counter in Greensboro.• Caryl Chessman, a sex criminal and kidnapper, loses his last appeal and dies in the San Quentin Prison gas chamber. UC-Berkeley march to the prison in protest.

• UC students and others are hosed down the steps of San Francisco City Hall during protest against the House Un-American Activities Committee.

1961

• Segregationists attack a Freedom Ride bus at Anniston, Ala.1962

• Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) is founded in Port Huron, Mich., as a left·liberal reformist organization.• Christian Anti·Communist Crusade comes to Oakland, but denunciations by clergy, congressmen and notable citizens begin the end of the Fred Schwarz version of the radical right.

• Compulsory ROTC, an issue for five years, becomes voluntary at UC.

• James Meredith enrolls at the University of Mississippi, first black student in Ole Miss history. Federal marshals fight off 4,000 white students and local segregationists in a riot that kills a newsman and a bystander.

1963

• The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom draw's 200,000 to hear Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. say, "I have a dream," and conclude, "Free at last."• Kennedy speaks at Charter Day rites at UC·Berkeley; activist groups picket in protest.

• A bomb in a Birmingham Sunday school kills four black girls.

• UC students remain largely uninvolved as Berkeley voters repeal a city open housing law, 22,720 to 20,325.

• The UC ban on Communist Party speakers is lifted. Mickey Lima becomes the first CP member to speak on the Berkeley campus since 1951.

• Berkeley CORE organizes equal·opportunity employment rallies at Mel's Drive·in in San Francisco (111 arrests) and Mel's Berkeley (180 pickets).

1964

• Aftershock from the killing of President John F. Kennedy in late 1963 leads to widespread cynicism when the Warren Commission concludes in September that a single crank, Lee Harvey Oswald, had been responsible.• The popular president had been succeeded by Lyndon B. Johnson. In August, Congress supplies him with war powers after reports that U.S. ships had been attacked by North Vietnamese aircraft in the Gulf of Tonkin. At the time, 150 Americans had died in Vietnam.

• In San Francisco, hundreds of UC students and other demonstrators are hauled off to jail from the Sheraton·Palace Hotel. Earlier demonstrations include a "shop-in" at Lucky stores and sit-ins, with arrests, in auto dealerships. Although demands are heard for punishment of students involved, UC President Clark Kerr says the university can't interfere with what students do off the campus — but students can't bring advocacy on campus.

• Dozens of UC students, including Mario Savio and Stephen Weissman, are among the 650 volunteers involved in the Mississippi Summer Project, organized by SNCC (Student Non·Violent Coordinating Committee), to help with registration campaigns that bring 40,000 black voters into the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party.

• Urban riots break out in Harlem and other cities, previews to the Watts riot of 1965 and the Detroit riot of 1967.

• In November, California voters kill the Rumford Fair Housing Act, Proposition 14, through a referendum.

• Johnson is elected by a landslide after creating "The Great Society" in a battle of slogans with Republican conservative Barry Goldwater.

• The year marks the first widespread distribution of LSD out of the laboratory and into the pads. The Beatles revolutionize pop music with a nationwide tour that includes San Francisco. Oral contraceptives become widely available.

San Francisco Examiner

December 11, 1984

Free Speech patrimony scatter to the winds

Agents of ChangeBy Lynn Ludlow and George Frost

Examiner staff writers

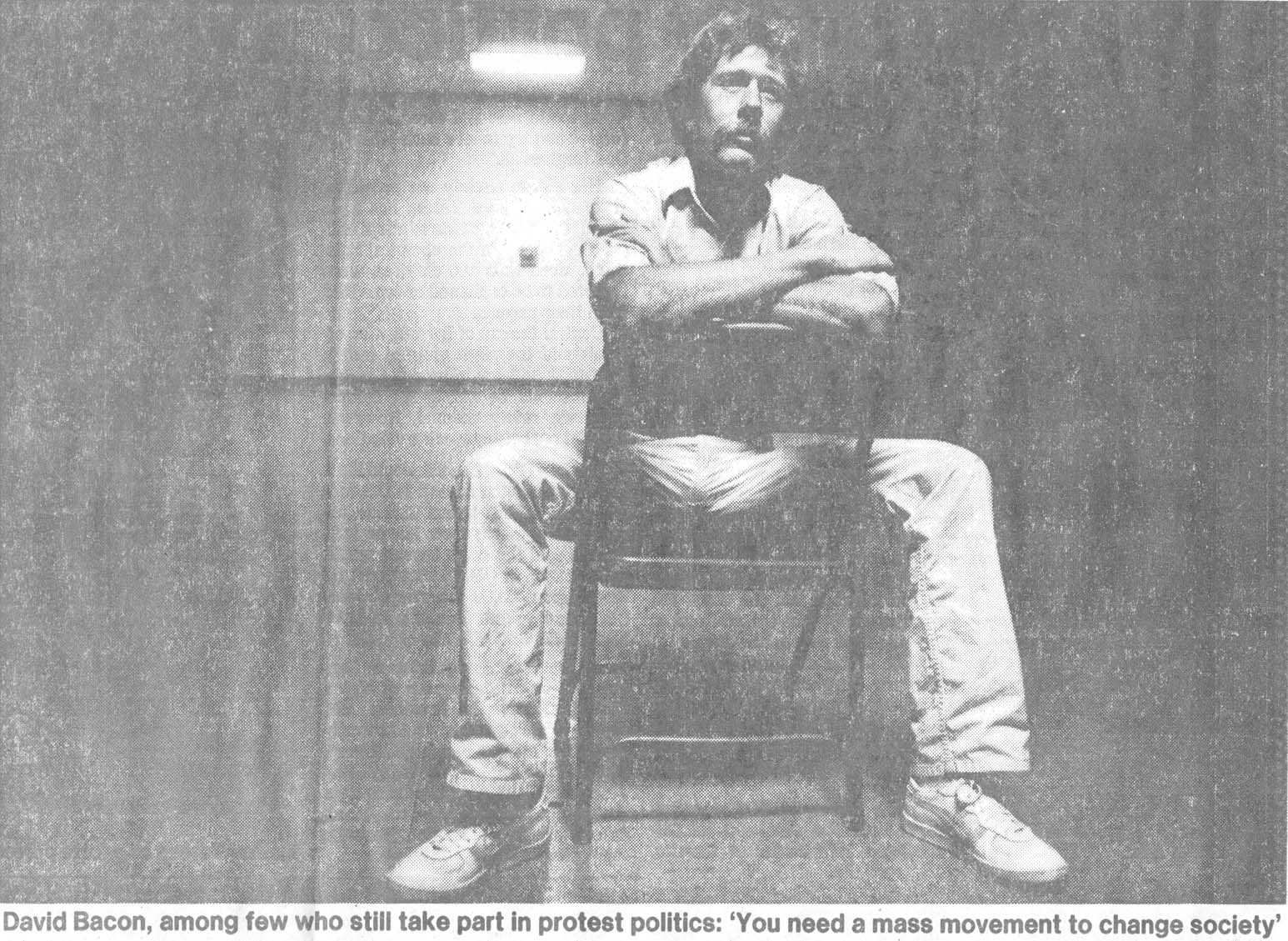

Third of six partsDavid Bacon, who 20 years ago marched into Sproul Hall, today recalls the "tremendous release of energy" that he associates with collective political action.

"People themselves are transformed," said the 36-year-old union organizer. "You are out there beyond the experience of everyday reality, opening up to change."

He waits.

Interviewed during an Examiner survey of activists arrested in the Free Speech Movement, Bacon doesn't have much company from his fellow demonstrators of yesteryear at the University of California in Berkeley. Twenty years later, few of them take part in protest politics, according to the survey.

Steve Gabow became disillusioned.

David Witt returned, he said, to the real world.

Michael Shub said mathematics, not politics, is his main interest

In the survey of onetime FSM activists, most said they haven't been arrested since Sproul Hall.

Most said they don't demonstrate, don't belong to "activist groups" and don't take an active role in electoral

—See Page A4, col. 1

Rank-and-file returned to the 'real world'

—From Page Al

politics. Many don't even vote.

"It still thrills me when I see a demonstration," said Kenneth Barten, 43, an alcohol education counselor in

Virginia. "I can empathize."***

The Big Chill"I didn't see it," said Patricia Eliet, 48, now a professor of English lit Cal State Dominguez Hills. "Deliberately not."

The 1983 movie is all about Harold and Sarah and Meg and Michael 8lld Nick and Karen and Sam and how they interact, as the saying goes, with the suicide of an unfocused but brilliant 1960s radical named Alex. Their idealism has faded.

Eliet said, "My understanding is that the movie is about revolutionaries turned Yuppies. I just don't care."

Lynne Hollander, now a clinical psychologist, was involved for more than 10 years in prison reform, civil rights and the Citizens Party.

"The people I know have remained active, although I myself am not particularly active now," said Hollander, 43, who is married to the FSM's best-known spokesman, Mario Savio.

"I am busy raising a child," she said. "Did you see 'The Big Chill'? It was a very good movie, but... Nobody I know is like that."

***

Scholars digging into the distant 60s tend to say activists have remained activists.

Joseph DeMartini, a Washington State University sociologist and author of "Social Movement Participation" said various reports suggest "former activists make up a disproportionate number of those involved in 1980s social movements."

But results of The Examiner survey don't jibe with this belief. The survey responses also conflict with expectations of FSM activists at the time. In 1964, surveyed by fellow student Glenn Lyons, first-time demonstrators agreed 2 to 1 they would become more active politically.

Wirt said he was "apolitical before the FSM and apolitical today." Now 40 and an an electronics engineer in Berkeley who works with rock bands, he said he was active at one time with the Progressive Labor Party. He quit, he said, because, "You have got to live in the real world. You try not to compromise, but..."

Shub, 42, a professor of mathematics at City College of New York, said, "It's a matter of time. Politics is not my major interest. Math is. And I have a kid I raise."

Gabow, 42, an anthropology professor at San Francisco State University, said he dropped out of the Socialist Workers Party but sometimes turns up for protests. He was among the 1,100 arrested this year at Lawrence Livermore Laboratory in anti-nuclear demonstrations.

Bacon, on the other hand, is involved in several causes at once. He demonstrates regularly. He has been arrested so often that he lost count.

"You need a mass movement to change society," he said. "To build a mass movement you need a core of committed activists."

***

Wendy Chapnick

She wasn't famous. Like most of the FSM demonstrators moved by the eloquent fury of their peers, Wendy Chapnick attracted little attention to herself when they filed into Sproul Hall.

She received a relatively light sentence ($150 fine, probation, no jail time). Graduated in 1967 with a degree in social science, she settled in Philadelphia and became a union staff member. Although ill with the flu in January 1973, Chapnick arose from bed join a protest delegation that stood in cold rain outside the inauguration ceremonies for President Richard M. Nixon's second term.

She came down with viral encephalitis, a complication of her influenza. Within 10 days she was dead. Her parents, still too grief stricken to discuss it, blame Nixon.

***

Once they marched with The Movement and raised their left fists in radical solidarity, but those in the survey sample said they are mostly (86 percent) registered Democrats who preferred Mondale (80 percent). A few (5 percent) are Republicans.

"I'm not an ardent Republican," said Berkeley attorney David Tussman, 38, whose father, Joseph Tussman, remains a member of the UC faculty. "But I believe Republicanism basically works better."

Bacon said he supported Gus Hall and Angela Davis, the Communist Party write-in candidates.

Barter, the man who says demonstrations thrill him, said he hasn't voted since 1964, when President Lyndon B. Johnson faced Republican contender Barry Goldwater.

"He portrayed Goldwater as a war-mongering maniac and turned around and escalated the war himself."

Although the 1964 sit-in is often described as the turning point for a generation of idealists, most (69 percent) choose in 1984 to express their idealism through other means. Many (29 percent) of the FSM alumni prefer to give donations.

"I guess I'm too busy with my life, my career, my family," said William J. Knight, 44, now a mathematics profesor in the Midwest. "I guess sometimes I have guilty feelings about that."

Mark Desmet, 42, who owns a computer firm in Mountain View, said, "CORE (Congress on Racial Equality) disappeared a long time ago. The antiwar movement dissolved when the war ended. I now support Amnesty International. With donations."

Relatively few ex-demonstrators (23 percent) say they are involved in "activist groups."

Julie Wellings, 41, a jewelry artist in Ojai, said, "I cannot afford the time."

Fresno physician John Reinsch said, "I always had trouble with the activist personality. Very few were unselfish, tolerant and giving."

Gordon Bergsten, an assistant professor of economics at Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pa., said, "At age 43 there are a lot of things I do differently today. Even basketball. My goals are similar. But my body is a little slower."

The survey produced but one unanimous answer. Every respondent said the FSM experience was worth it.

"I wouldn't have missed it for the world," said Michael Cortes, 42. "I had intended to play violin chamber music. I wound up getting a degree in social action."

***

Sara Davidson Now a well-known writer, she was a member of the Class of '64. Although she missed the FSM itself, she described protest days in her novel, "Loose Change," a fictional account of three onetime roommates in a UC sorority.

"In Susie's memory, the years from 1965 to 1967 are a jumble of meetings, teach-ins, marches and talk, endless talk. "Words were changing so fast. Negroes became blacks. Libcrals became scum. God was declared dead.

"There was a New Morality, a New Journalism, a New Music and a new way of looking at everything, and out of it all, a New Left!"

***

Most of them would do it again, given the same circumstances.

"There was something poignant about the Sixties," said Lee Goldblatt Nixon, 41, a former teacher in San Rafael. "There was a desire for a more humane state, a spiritual hunger." This hunger has long fascinated Michael Rossman, a Berkeley writer who. calls himself "the FSM's chief mystical propagandist."

He wrote, "We were cast into a desperate spontaneous democracy, which was our ultimate and only magic,"

Mario Savio said, "For a moment all hypocrisy was swept away and we saw the world with greater clarity than we had before."

Saul Landau wrote, "What enlivened the FSM was the exhilaration of feeling that you were, for once, really acting, that you were dealing directly with the things that affect your life, and with each other."

From this experience came the New Left, as it was called, which spurned at first the doctrines, feuds and rivalries of Marxist groups on campus. During FSM days, the Old Left organizations for students included the W.E.B DuBois Club (Communist Party), Young Socialist Alliance (Socialist Workers Party), May 2nd Movement (Progressive Labor Party), Independent Socialist Club (Trotskyist) and Spartacist Youth League.

Instead, demonstrators of 1964 defined The Movement through action, "The idea was to put your own body on the line," said Rodney Mullen, 41, a former Synanon official who now administers an alcohol-rehabilitation center in Arizona.

Students for a Democratic Society, which had come to represent the changing New Left, collapsed in 1969 after a ruinous convention fight. It was won by the faction called Weatherman, which went underground with a program of bombs and bullets.

Many FSM veterans said the New Left led to more positive causes, such as the women's movement, which came of age in the 70s, and the anti-nuclear movement, which has gone back to the civil disobedience tactics of 1964.

Bacon, now a veteran activist, said the FSM was important.

"It woke up students across the country. It brought the Vietnam war to the fore. Students brought the tactics of the civil rights movement to Berkeley. It helped write an end to McCarthyism. It served as a model for later actions," he said."

(Demonstrators against apartheid policies in South Africa marched last week to the statewide administrative headquarters, University Hall, to protest the university's links with South Africa; 38 were arrested.)

Only 16 years old during the FSM, Bacon said he learned that political commitment has consequences. he said he was beaten after his arrest and held in solitary confinement without clothes.

"It made me a more committed person," he said. "When thousands of people get together, like the FSM or the farm workers, you realize you can change the world."

For a few other FSM veterans in the survey group, protest became a way of life.

They include Big Bill Miller, known also as Buffalo, who stands 6-5 and lives in Monte Rio. Never a UC student, Miller said he has been arrested in attempts to block the troop trains in Berkeley (1965), at the Navy recruiting table on campus (1966), at Provo Park (1968) and many other occasions.

***

Civil Disobedience

He had been arrested often in non-violent demonstrations. He was noted as a quick and ruthless debater in Sproul Plaza. Friends said he wasn't really arrogant, just shy. He was dragged out of Sproul Hall.

They say he began dropping acid in the late 60s after he had founded an underground newspaper in San Francisco, It vanished. Word came that his wife had divorced him. He moved away.

Ten years later, on a Saturday morning in 1978, BART police reported that a man in his 90s had tried to kill himself by jumping in front of a train at the Rockridge Station. It was the same ex-activist who came back to Berkeley to die. Instead, he fell unhurt between the rails.

Officers switched off the third rail. They approached the would be suicide to escort him to a psychiatric clinic.

He went limp.

***

Many FSM activists said they left the movement when it turned from civil disobedience to more violent forms of protest.

Mullen said the development was no surprise.

"In some ways violence was a natural development with people getting arrested all those times. Some said, 'I'll fight back.'"

Reporters standing outside Sproul Hall in 1964 could see Oakland police dragging limp demonstrators down the marble stairs. After the windows were covered, reporters could still hear the thump, thump, thump.

Wirt said he was reclassified 4F in the draft because of the way he was arrested in Sproul Hall.

"The cops were dragging people off, and I climbed up on somebody's shoulders to take a picture," he said. '''This cop grabbed my neck in the crook of his arm and held me off the ground. It crushed a disk in my neck."

Bacon compared The Movement with a train.

"You don't know where it's going to go. Or if you're going to win or lose. You're outside the pale of society. You have to find new friends, ask new questions. You start this train going and you have a sensation of movement, as if you're going somewhere.

"While taking responsibility for your actions, the movement becomes part of you, and you are partly responsible for the movement. It teaches you the unimportance of individualism. Those who tripped out on themselves came to a rocky end."

***

Commitment Shelagh Hickey Covington, a Chicago civic leader, said: "So, yes, I learned how satisfying and exciting deep commitment can be." Pause, "I'm rambling," she continued, "because a small child is tugging at me."

•

PRESIDENTIAL PREFERENCE

(figures in percent)Mondale …………. 80

Reagan …………... 10

Other …………….. 10

based on a representative sample of FSM activists.Remarks:

I'd say for the Democratic guy. Who? Mondale?

—David R. Wald, cabinetmaker"Gus Hall and Angela Davis."

—David Bacon, union organizer"I'd like to see a wider spectrum of alternatives."

—Gordon Bergsten, economics professor"No one. I would have voted for Jackson if he had been nominated."

—Mark Desmet, computer programmerVOTING HISTORY

(For president; figures in percent)U.S.•• FSM•

1980

Carter ............ 20 66

Reagan .......... 43 5

Other ............. 13 10

Didn’t vote … 24 311976

Carter ......................... 54

Ford ............................. 2

Other ......................... 10

Didn't vote ................ 221972

McGovern .................. 65

Nixon: .......................... 2

Other ............................ 2

Didn't vote .................. 31

• A representative sample of FSM activists.

•• A nationwide sample

comparable in age, race and education.POLITICAL DEMONSTRATIONS

(figures in percent)Yes ………………….. 19

No .............................. 69

Occasionally .............. 10

No answer..................... 2Remarks:

"I nearly did last year. The occasion was the 15th anniversaryof the assassination of Martin Luther King, But we got bumped off the bus at the last moment."

—Gordon Bergsten, economics professor"Fury is a wonderful thing if it can be channeled."

—Mark Switzer, environmentalistbased on a representative sample of FSM activists.

ACTIVISM TODAY

(figures in percent)Still involved in activist groups?

Yes ………………….. 22

No .............................. 78Reasons for non-activism

Lack of time ………………. 9

Lack of motivation

or interest ………………... 5

Interested in personal

not social change ……….. 19

No longer active

but contributes money ….. 29

No longer believes

activism is viable ………… 7

Issues are not

important enough …..…….. 2

Plans to become

active again ………………. 5

No answer …..……………. 24Tomorrow: The Education Factory

FSM leaders keep the·faith: 'Still agitating' after all these years

By George Frost

Examiner staff writerBettina Aptheker, often accused of leading the Communist Party contingent of the FSM, readily admits it.

With one proviso.

"Actually," she said, "I was the only Communist in the movement."

Today she is a dropout from the party.

A teacher of women's studies at the University of California at Santa Cruz, she said that feminism, not communism, is the focus for her political activism.

Her break from the party came about five years ago, she said, when the party's publisher objected to the feminist outlook of a book she had written.

She called it a difficult personal decision because it meant a break with her family.

The daughter of Herbert Aptheker, a man invariably described as a Communist Party theoretician, she said her upbringing in Brooklyn was unconventional and highly political.

At age 16 she walked her first picket line.

During the FSM, she said, she had "no conception of a woman-oriented perspective" and said her social life back then was confusing.

"I was treated just like one of the boys," she said. "Of course, I wasn't."

The women's movement, she said, grew partly out of a rejection of macho '60s politics.

"Women did most of the basic work, filing and sorting," she said. "Men got the publicity and made the decisions."

She is at work on a sixth book, "A Labor of Love: Women's Consciousness and the Meaning of Daily Life."

"Through women's studies, I combine the teaching with a kind of activism, sometimes anti-war, or anti-racism —but it really stems from my women's work," she said. "That is my center."

•

While she doesn't spend most of her time marching, picketing and blocking the corridors of power, Aptheker's quiet activism appears typical of the FSM leadership of 1964. Now in their 40s, with careers to pursue and families to worry about, most of them remain active in efforts to bring change.

They work for a variety of causes: feminism, trade unionism, peace, environmentalism and others. The struggle, they say, goes on.

•

Peter Franck, a San Francisco attorney who specializes in entertainment and copyrights, said he relishes his days as a student radical.

With fervor, he said, "We worked together to change society."

Franck co-founded the prototype Berkeley student activist group SLATE in 1957. It raised money for Freedom Riders in the South, staged peace marches, protested the House Committee on Un-American Activities hearings in 1960, opposed compulsory ROTC, picketed businesses in behalf of equal employment opportunity and worked for changes in campus rules that barred activist politics.

"The FSM was an extension of the political action of 1957 on," he said. Unlike the FSM, he said, which enjoyed mass student support but had little infrastructure, SLATE members built an organization.

Many former members, he said, are activists "through our professional work."

Franck is president of the Pacifica Foundation, which operates member-supported Berkeley radio station KPFA and others. The foundation suppports lobbying and legal action against the networks to stanch what he calls the violence, sexism and racism coming from the tube.

"We are trying to make the mass media accountable to those they serve"

•

Jack Weinberg, the FSM's tactician, coined a '60s slogan when he told a reporter, "We have a saying in the movement, 'Don't trust anyone over 30.'"

He is 44.

Today, he said, young activists should reject their elders, even venerable veterans of the FSM.

Weinberg, who calls himself a permanent activist, was recently laid off at a steel mill in Gary, Ind. He said he seeks a new career.

He has worked for a halt to construction of an Indiana nuclear plant, for environmental causes and for the Democrats during the past presidential campaign.

The legacy of the FSM, he said after an October reunion this year in Berkeley, became "a crushing burden for young people today."

He said, "When we were in the FSM, there were no antecedents, no one telling us what to do."

Each generation, he said, must create its own unique form of activism.

•

Stephen Weissman, usually considered the chief strategist of the FSM, is now a writer and film producer in London. His latest projects include a book, "The Islamic Bomb," and a film about guns in America.

•

On Halloween, Mario Savio took his 4year-old son trick-or-treating in their Russian Hill neighborhood. The boy was costumed as Superman.

It's been an uneventful life for Savio, 43, who is now a graduate student and teaching assistant in physics at San Francisco State University. Most of the students have never heard of him. This is OK by him.

In 1964, Savio's eloquent fury inspired thousands of students with his call to "throw yourselves upon the gears ..."

After the '60s came silence.